This was published in the DNA newspaper on 23rd June 2018

The Indian Rupee (INR) is back in headline news. Thanks to a sharp upturn in global crude oil prices and an expansion in India’s current account deficit (CAD), INR has been under pressure for the last couple of months – depreciating against the US Dollar (USD) by ~5 per cent year till date. After a period of remarkable stability for three years, depreciation of INR has caused renewed flutter in the popular media over both the level of INR and how much it could depreciate by in the near future.

The issue though, cutting through the noise, is whether this is abnormal? Or is it merely a reversion to the normal? Is it something that is desirable? Or do policymakers (government, RBI etc) need to do something about it?

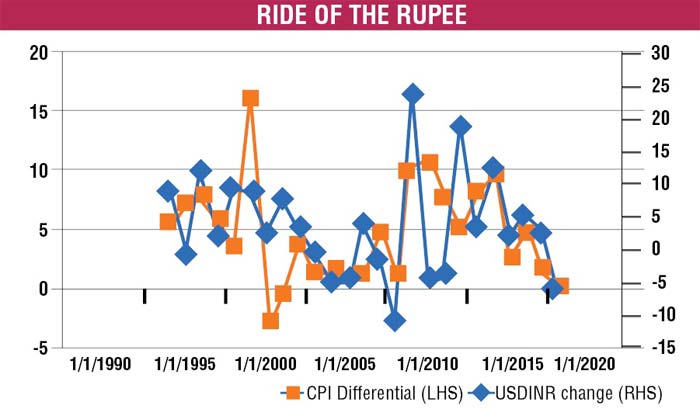

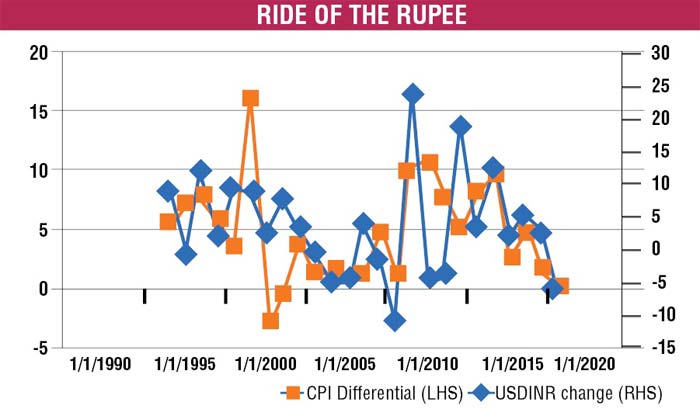

First things first, structurally, at the core of currency valuation, is the fact that appreciation (or depreciation) of a currency against another currency reflects the inflation differential between the two economies. Intuitively, this makes sense – if India runs an inflation of, say, 6 per cent, and the US runs an inflation of, say, 2 per cent, over the course of a year, a unit of Indian currency would be worth 4 per cent less than a unit of US currency. Over long periods of time, this relationship holds out as the chart shows.

There is nothing fundamentally wrong in a developing economy like India running a somewhat higher inflation than a developed market like the US. Ergo, a certain amount of currency depreciation is structurally built into India’s current development stage. So, what is there to panic about?

The issue, outside of a small group of people who conflate level of the currency with economic virility, isn’t with the depreciation per se, but the volatility associated with currency movements. INR, for example, gained against the USD in 2017 by 5-6 per cent. Now when it has shaved off all that gain in a matter of 2-3 months in 2018, a lot of market participants (and observers of the market) are getting worried. What they are really spooked by isn’t, therefore, the level of INR, but by the volatility associated with its price movements.

Is low volatility a good thing? The RBI has a stated policy of dampening the volatility of INR, without really determining a specific level of the currency. This is a practical stance in most parts as high volatility hurts the ability of operating businesses to adjust with the level of the currency. There is never a free lunch though, and RBI’s policy of keeping volatility low also leads to a build-up in market complacency. Since the “taper tantrum”-led crisis in 2013, there has been a large build-up in Foreign Portfolio Investor (FPI) holdings in Indian debt securities. A vast majority of these investments, $65-70 billion at last count, are the result of “carry trades”. In simple terms, FPI investors have invested this amount because of a) the large differential between the interest rates in India and the US and b) an assumption that INR will not be very volatile, and hence preserve the USD value of investments long enough for them to make a profit in USD terms. The second assumption is key and predicated on the assumption that there won’t be sudden, large depreciation in INR. Typically, such complacent assumptions by the market tend to result in excesses getting built into the system during good times, and driving up the underlying asset price (INR in this case) beyond the fair value of the asset. And when macro conditions turn for the worse, these excesses tend to be violently corrected, sometime leading to panic and disruptions.

This then begs the question: Is INR over-valued? Or fairly valued? The bellwether benchmark for estimating value of INR has been RBI’s Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) Index. A level above 100 nominally represents INR to be overvalued, while a level below 100 would be undervalued. From a peak level of 121, the REER is hovering around 115-116 now. Which means that theoretically, INR is still overvalued. However, real life is seldom congruous to theory. There are multiple policy imperatives – a lower level of INR makes for more expensive imports, driving up inflation and, therefore, interest rates. On the other hand, it also reduces demand for imports, and allows domestic industry some headroom to replace the imports with locally manufactured substitutes. There are no easy answers, but on balance, the question of valuation is somewhat moot. What businesses and consumers are most affected by is shocks, rather than direction. If the natural direction of INR is to take it lower than its current levels, it shouldn’t be a policy imperative to stop its journey, but merely to regulate its spikes.

In the recent past, there have been radical solutions suggested – including a large FCNR(B) deposit raising by RBI, similar to the one done in 2013 – in order to shore up the currency. By most available indicators though, it is a call to action in order to be seen to be doing something, rather than something that is direly needed to be done. A falling INR isn’t a reflection of India’s economic strength, it merely recognises a financial reality. Neither panic nor complacency is an appropriate policy response.

No comments:

Post a Comment