This article was published in the DNA, dated 27th of Jul, 2017

In the recent Unified Commanders’ Conference, the Indian military has reportedly asked for an allocation of Rs 26.84 lakh crore for the next 5 years. To put the figure in context, this represents a number that is almost triple of the previous five years’ allocation. The annual simple average of the demand made this time (Rs 26.84 lakh crore over 5 years) would be double the defence budget allocated for the current fiscal (Rs 2.74 lakh crore). The numbers, analysed whichever way, are staggering.

Let us look at the headline numbers. At current levels, defence expenditure constitutes 2.1 per cent of the GDP. Assuming a 10 per cent nominal growth in GDP (6-7 per cent real GDP growth plus 3-4 per cent deflator, or inflation), the demand for 26.84 lakh crore represents 3.3 per cent of total GDP generated over the next five years. Realistically though, expenditure cannot go up overnight from 2.1 per cent of the GDP this year to 3.3 per cent next year. They will go up gradually, with a “hockey stick” (exponential) increase towards the latter half. However, that also means, given the same numbers (expenditure demand and GDP, over five years), the ratio will likely touch 5-6 per cent in 2022. Very few countries that could manage to sustain such levels of 3 per cent of GDP over 4-5 years in the late 80s ended up with a bankrupt treasury in the 90s.

Next, how do these numbers stack up on a global comparative basis? It’s an old chestnut in military policymaking, ie, India doesn’t spend enough on defence. Is that correct? There are two benchmarks typically used.

First, defence expenditure as a percentage of GDP, popularly used, but largely limited in its real policymaking import, as it is not truly reflective of fiscal affordability. As per the World Bank, the numbers stack up as follows: China (1.94 per cent), East Asia-Pacific (1.73 per cent), European Union (1.48 per cent), Republic of Korea (2.64 per cent), Pakistan (3.55 per cent), Russia (4.86 per cent), Turkey (2.13 per cent), Israel (2.38 per cent) and US (3.30 per cent)

India’s very much in the global ballpark. We are higher than China (and Asia-Pacific average), lower than Pakistan, and in the same range as Turkey and South Korea (both having complex military challenges). Major countries that spend significantly more — US, Russia, Israel — are characterised by very large domestic Military Industrial Complexes (MIC). Military expenditure accounts for large investments and employment in these economies. The situation is quite the opposite in India.

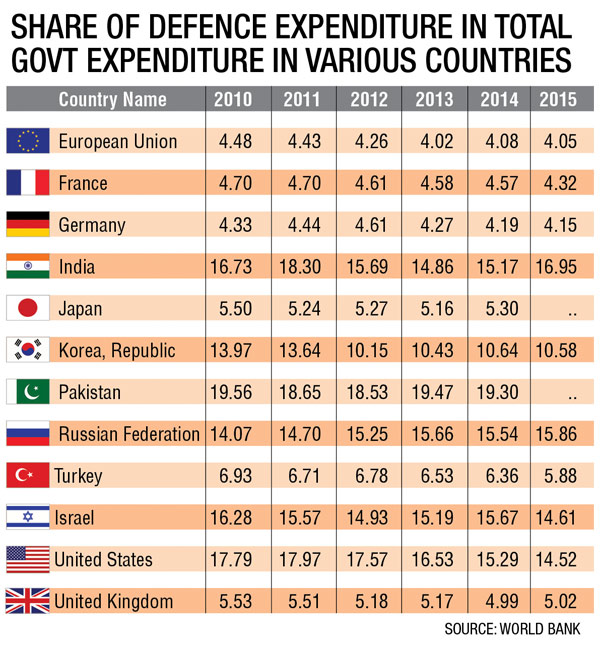

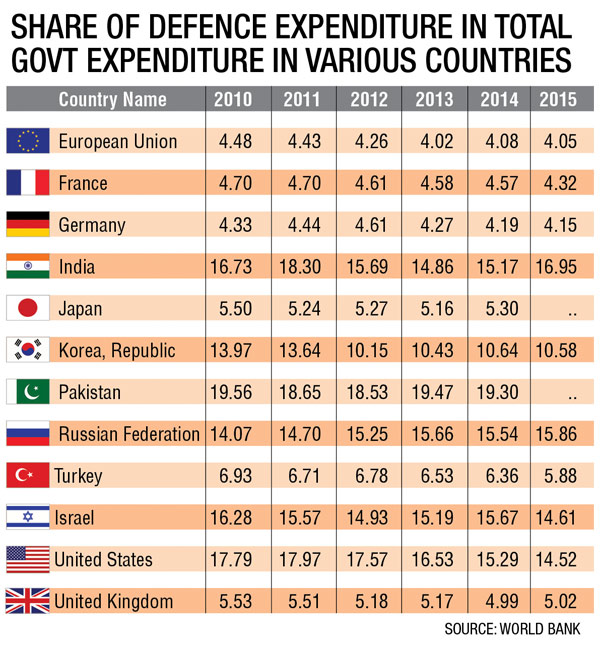

Second, share of defence expenditure in total government expenditure — less popular, but a lot more insightful for policymaking, as it reflects fiscal constraints.

It is here that the real constraints become starkly visible. India already spends a very high proportion of government revenues on defence. In fact, defence is the single biggest item in the Union Budget, outside of debt servicing.

The only major country higher is Pakistan. In a country with significant deficits in social and economic capital, the fiscal space for a bigger share of the pie for defence simply does not exist.

Lastly, India’s high import-intensity of defence expenditure makes it an inefficient medium to channelise Keynesian boosts to the economy. With 70 per cent of all defence capital expenditure spent on imports (India’s been the top weapons importer in the world now), and low multiplier on military imports, the ability of policymakers to allocate part of government “pump priming” expenditure to defence is absent.

In a nutshell, plans with numbers like Rs 26.84 lakh crore are pipe dreams rather than effective plans. On top of that, we have a severe issue in terms of quality of military spends.

In the last 5-6 years, 45-50 per cent of the defence budget has been spent on personnel costs (salaries and pensions). This component is expected to grow exponentially, thanks to more “boots on ground” — Indian Army has expanded by 25 per cent in the last 15 years. And, now the new big daddy of Budget Expenditure is OROP. Increase in personnel costs in the years to come would far outstrip nominal GDP growth.

This is not new, or even surprising. A generalist MoD bureaucracy and a (largely) hands-off political class have let the military get away with fantastic wish lists in the name of planning. Unless structural changes are brought about in organisation and management, we will continue to have hopes as plans in India’s military.